I’ve been beavering away on the keyboard in the office at the Trust HQ, Banovallum House, and haven’t had lots to write about, however I’ve recently been out on a few visits so it seemed the right time to continue my blog.

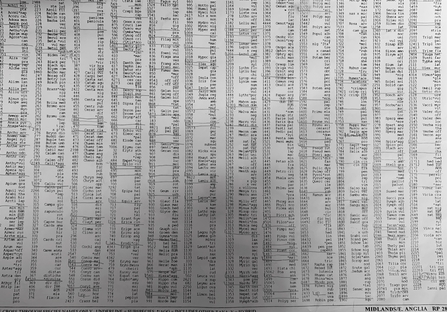

The office work I’ve spent most of my time on has consisted mostly of data entry from the Wildlife Site Officer, Jeremy Fraser's botanical-surveying site visits throughout the year.